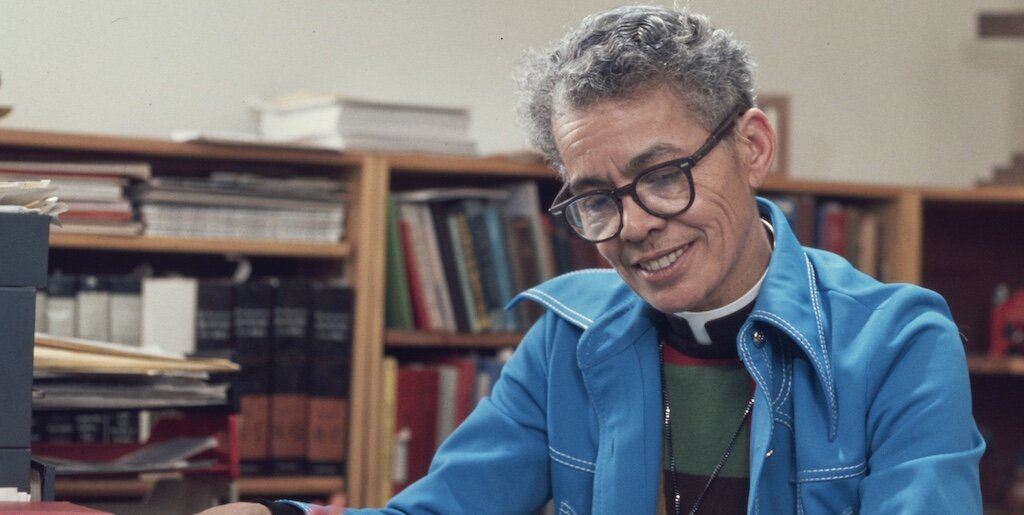

An Interview With Pauli Murray (1976)

An excerpt from Southern Oral History Program Collection’s Genna Rae McNeils interview with Pauli Murray in 1976.

A conversation between historian Genna Rae McNeil and Pauli Murray on February 13, 1976.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

In connection with the goal of the Southern Oral History Program, namely studying individuals in the South who have made significant contributions to various fields of human endeavor, the following is an interview conducted by Genna Rae McNeil, assistant professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, February 13, 1976 with Pauline, better known as "Pauli," Murray. Pauli Murray is a distinguished American Negro [her preference] who has been involved in the struggle for civil rights for blacks, women's rights, equal rights, in other words, the struggle for human rights, qua: writer and poet, activist, lawyer and professor since the 1930s.° Dr. Murray comes from a family of educators.

Her maternal grandfather, who was one of the first students of Asmun Institute, later renamed Lincoln University, helped to establish schools for freed blacks in Virginia and North Carolina following his military service for the Union forces in the Civil War. Her father was a principal in the Baltimore public schools and her aunt and namesake, Pauline Fitzgerald Dame, taught many years in the city school system of Durham, North Carolina. Although Dr. Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland, shortly after the sudden death of her mother, she moved to Durham, North Carolina to live with her Aunt Pauline's family headed by her maternal grandparents, Robert G. and Cornelia Smith Fitzgerald.

There she was raised to be a strong individual and an independent thinker. There she was nourished with stories about her family, her heritage, and taught to have pride in her racial identity, which necessitated walking straight and tall in "proud shoes" despite feelings and obstacles.

Therefore, after attending segregated schools through grade eleven in Durham, North Carolina, Ms. Murray went on to seek higher education in nonsegregated schools. She earned an A.B. as an English major at Hunter College in New York in 1933, an LL.B.cum laude at Howard University in 1944, an LL.M. at the University of California, Berkeley in 1945, and an S.J.D at Yale University School of Law in 1965.

She has published numerous books and articles on a variety of subjects, States Laws on Race and Color, compiled and edited by Ms. Murray in 1951, Proud Shoes: The Story of An American Family, published in 1956, The Constitution and Government of Ghana, 1961, co-authored with Leslie Rubin, and a book of poetry, Dark Testament And Other Poems in 1970, although most of these poems were written between 1933 and 1941. Articles include, "The Negro Woman's Stake in the Equal Rights Amendment," which appeared in the Harvard Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Law Review, 1971 and "The Liberation of Black Women," which appeared in Joe Freeman's Women: A Feminist Perspective, 1975, and other feminist anthologies. She is presently working on a new book under the working title, The Fourth Generation of Proud Shoes.

As an American Civil Liberties Union lawyer and member of the board of directors, whe has contributed to federal court decisions recognized as precedent-making with regard to sex discrimination, namely, the litigation White vs. Crook in 1966 and Reed vs. Reed in 1971.

Her honors and awards include the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, 1944-45. She was named Woman of the Year by the National Council of Negro Women and Mademoiselle Magazine in 1946 and 1947, respectively. She was awarded an LL.D. degree by Stonehill College in 1967, Northeastern Massachusetts. In 1970, Howard University bestowed her with the Alumni Award for Distinguished Post-Graduate Achievement in Law and Public Service.

She was listed in the World's Who's Who of Women, named to the Hall of Fame of Hunter College Alumni Association and recipient of the degree of Doctor of Science from Lowell Technological Institute in 1973.

Moreover, a biographical sketch of Dr. Murray will appear in the 1976-77 Who's Who in America. Finally, I would be remiss if I did not mention that the various positions held by Dr. Murray include Deputy Attorney General, Department of Justice, California; Associate Attorney at the renowned Paul, Wise, Rifkind, Wharton and Garrison firm of New York City; Senior Lecturer at the Ghana Law School, Accra, Ghana; member of the President's Commission on the Status of Women; Vice-President of Benedict College; and Professor of Law and Politics at Brandeis University.

Dr. Murray, I would like to begin with your family background and a quotation by someone very dear to you: "The past is the key of the present and the mirror of the future. Therefore let us adopt as a rule to judge the future by the history of the past, and having the key of past experience that has opened the door to present success and future happiness."

PAULI MURRAY:

That was in my Grandfather Fitzgerald's diary.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Yes, 1867. July, 1867. I have several questions about your family background. First of all, although you were born in Baltimore, Maryland, during your childhood, in a real sense you became a North Carolinian. I would like to know something about your ties to Chapel Hill and Durham, North Carolina. Specifically, I have questions, although you have gotten much into Proud Shoes: The Story of An American Family, I would like to know first of all, something about your parents, who they were, and although we know that your mother died at an early age, what you can recall of your mother, what you recall being told about your mother, and what you recall of your father.

PAULI MURRAY:

[Showing a picture] Well, those are my parents. That picture was taken the year that I was born, 1910. I think that it was taken very shortly after my birth. My mother was Agnes Georgiana Fitzgerald Murray and my father was William H. Murray. He was a teacher in the Baltimore city public schools and was also a principal. She was one of the early graduates of Hampton School of Nurses …or Hampton Training School for Nurses. She graduated in the class of 1902.

My mother died when I was a little over three and there were six of us, four girls and two boys. I'm number four down. The oldest girl was about nine when my mother died and the baby was about six months, a baby brother. The ages were spaced so that the three of us were really babies at the time of my mother's death. I was three, my younger sister was about twenty months, my baby brother was about six months, and something had to be decided about the three babies of the family. The three older children stayed with my father and my mother's oldest sister, Pauline …who you recognize in Proud Shoes as Mary Pauline Fitzgerald Dame, was both my namesake and my godmother.

She had kept me for periods of time before my mother's death and my father, in a sense, gave me to Aunt Pauline; but I understand that I was allowed to make the choice. I was asked, the day after my mother's funeral, if I would like to go with Aunt Pauline or if I would like to stay with the other children, which meant staying with my father, brother and two sisters. I am told that I said, "I want to go with Aunt Pauline," and that I broke into tears. In adult reflection, I would say that this shows the child that was pulled between wanting to identify with family and at the same time, this sense of loyalty and clinging to this aunt for security. In a sense, this is a history of my life, being pulled between my family and other things.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

There was nothing about the experiences of the family in Baltimore that made you want to leave that particular town, was there?

PAULI MURRAY:

Well, I was so young that it would be hard to say. I would not remember anything. I think that perhaps I may have experienced and understood more than I remembered. My mother died suddenly with a cerebral hemorrhage and this must have been a very painful and traumatic experience within the family. I may have blotted out the memories of it. My guess is that in that kind of tragedy, the mother just dying suddenly, that I reached out to the one person that I felt secure with.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Had you seen your Aunt Pauline often?

PAULI MURRAY:

She had kept me for about six months when I was about eighteen months old.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, she was in …

PAULI MURRAY:

She was in Durham, teaching.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

She didn't come to Baltimore, your parents brought you to Durham?

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes, well, during the period …during my parent's married life, the ten years of their married life, there was a great deal of visiting back and forth. My mother would come home with the children, Aunt Pauline would go up and spend summers with her after school was over. Aunt Pauline had introduced my parents and she felt a strong responsibility for them. They both loved her dearly.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

She was a matchmaker for them?

PAULI MURRAY:

Well, she was a kind of matchmaker, confessor, older sister, Rock of Gibralter. She was with them in all kinds of family crises and of course, I was named for her. So, she would obviously have a great sense of identification with her little namesake. For some reason, she cared very deeply for me and I think that she wanted very much to take me. She had lost both of her own children …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Childbirth or …

PAULI MURRAY:

Her little girl lived for about a week, and I don't know what that might have been. The little boy died of meningitis at nine months, so you can see that …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

So you certainly met needs for each other.

PAULI MURRAY:

Right.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Can you tell us what it was like growing up in the Durham-Chapel Hill area. Did you move around or were you in one place most of the time?

PAULI MURRAY:

No, I grew up in Grandfather's house. Grandfather Fitzgerald's house, which again you will recognize in Proud Shoes. There's a whole chapter talking about Grandfather's house and it's still there, by the way, on Carroll Street. I lived in Grandfather's house which meant, more or less, that I was a very small child with four to five very settled adults. Living in Grandfather's house and being a part of a larger family, an extended family …in those days, the Fitzgeralds and their kin were legion …gave me a sense of real roots and security. On the other hand, I had a different name, I had my own family, of which I was very conscious, and in some ways, I was alien. I felt very much a part of the house, I was made to feel a part of the family, I knew that I was a Fitzgerald descendent and yet, there was always this longing for my family, my brothers and sisters, and a kind of …I guess "sadness" about not having parents.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Did you visit your own family very often?

PAULI MURRAY:

Not until five years later and I only visited them, I think, once during my childhood. I was not very congenial with my Murray elders. [Laughter] I was one child, independent, had a point of view, had been permitted to assert myself and I think that my uncle and aunt, who were my father's sister and brother, by that time having five children, five Murray's to take care of …my father became ill and was in the hospital …had a kind of discipline to which I was not accustomed.

A rather rigorous kind of discipline. I was given a considerable amount of freedom for a child of those days. Aunt Pauline was a public school teacher, taught anywhere from the first through the fourth grade and a real disciplinarian, but had great sensitivity to children. I don't recall ever being suppressed in terms of "Shut up, don't you speak, children should be seen and not heard," or anything of the sort. I was allowed, I think, full self-expression, coupled with work discipline. I always knew that I had certain tasks to do and those tasks had to be done before I could do anything else, before I went to play.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Before I ask any more questions specifically about the important members of your family, I would like to get something about what it was like to be in Durham. You describe it in Proud Shoes as a village something like a frontier town and you said that while there was considerable prejudice, "that there was recognition of individual worth and bridges of natural respect between older white and colored families of the town." Now, was this something that only hindsight made you realize or was this something that one could be aware of even in adolescence?

PAULI MURRAY:

No. The quotation that you are giving there was my characterization of post-Civil War Durham in the latter part of the nineteenth century. I am really there talking about the climate in which my parent's generation, my mother and her sisters and brother grew up in and the time in which my grandparents and their generation were in their prime. Durham being this really post-Civil War town, it did not exist before the Civil War, so it had no background tradition of slavery and the Confederacy and all this sort of thing, and it being this kind of frontier town, it meant that people like my grandfather and his brother, my great uncle, Richard Burton Fitzgerald, coming into the town and being resourceful businessmen, had a rough respect of their white counterparts. And this would be true of families.

One would recognize the Fitzgeralds, along with maybe the Hills and the Carrs and the Dukes, not necessarily …when I use these terms, not suggesting that there were any social contacts between them, but simply a recognition that these were hard working, respectable families, good solid citizens of the community. And there was this rough respect.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, do you say that this continued?

PAULI MURRAY:

I suspect that by the time I came along it was not the same. You know …oh, I am trying to think of our historian who wrote The Nadir …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Rayford Logan.

PAULI MURRAY:

Rayford Logan, he talks about the nadir of Negro life and around 1900 to 1915 was simply the lowest, the very lowest ebb, and I think that I came along in Durham, and I came to Durham around 1914 when I was about three, I imagine that I grew up in sort of the aftermath of that lowest period, in which segregation had now become legal …somewhere between 1900 and 1910, you know, all the segregation laws began to pile one on top of another …and therefore, everything was clamped down tight in terms of rigid legal segregation of the races, lynching was still continuing, perhaps not as intense as it had been earlier, but it was still done and you would get maybe fifty or sixty people a year being lynched and lynching was something always in the background. You know, the terror of lynching was always in the background. The awareness of the Ku Klux Klan was always in the background.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

At what point in your life did you become sensitive to these kinds of racial distinctions, primarily the restrictions and the terrorization of this violence that was a part of being an Afro-American or a Negro or a black in the town? And then also, were you aware of color distinctions, that is, between mulattos and the darker and did this make any difference at all in terms of the Durham community?

PAULI MURRAY:

Let me see, let me answer these one by one. I suppose this awareness to a child of my generation grows with you just like almost a part of your body and your being. It is hard to say when you become aware because you take it in all of the time. I don't remember, for example, lynchings being prominently portrayed in the newspapers, but we would hear about them by word of mouth. You know, [whispering] "Somebody got lynched over in So-and-So County last night." I think that sometimes, they were even suppressed in the newspapers, but one was aware of it. It was something that one was aware of. Awareness of segregation …of course wherever you went in town, you saw the "White" signs, the "Colored" signs, drinking fountains, anytime that one would go down into the public center of town, one would be very, very conscious of it. Obviously, one would be conscious of separate schools and separate churches and the older people talking. It's something that you simply grow up with. It's not something that you suddenly experience. Now, there may be particular experiences.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

So therefore, you had no particular experiences such as Benjamin Mays or Malcom X., who might have had a Ku Klux Klan experience, that kind of violence perpetrated upon the family immediately or directly?

PAULI MURRAY:

No, only my grandmother's and my grandfather's memories, my grandmother would tell me about the Ku Klux Klan riding around her little cabin up in Chapel Hill and how sometimes she would get up at midnight and walk the twelve miles to Durham because she was afraid to stay there. This was during Reconstruction times when apparently the Ku Klux Klan was not very happy to have a person of color owning property. But for myself, not probably until I was about eight or nine did I have any experience that dramatized it for me. As a girl, obviously there would be a certain kind of protected life, I would not be as much …I wouldn't be as free to roam or to go around by myself, let us say, as probably the males were. Also, I would be probably less the target of male aggression, white male aggression, as a girl.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Well, I wonder, your mixed heritage and the whole issue of color in your family, did this cause any particular problems growing up in Durham …

PAULI MURRAY:

Oh, yes. [Laughter]

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Problems that were not the same kinds of problems of someone who came from a strictly black heritage and would not have this experience?

PAULI MURRAY:

Well, one of the ways that it showed itself …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

I think of Harriet, you know.

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes. One of the ways that it showed itself was that I was one of three …the term that they used to use in those days was "light skinned children." Christine Taylor, whom you know as Christine Morris, Lucille Johnson, whom you know as Lucille Johnson Hancock. She is a retired school teacher in Durham.

Now, if you recall those types, you know Christine, here were children of …I was much less so, but here were children who were almost indistinguishable from Caucasian children and wherever you are a minority, you know, whether you are a fair skinned minority or even if you are a white minority, a Caucasian minority among black kids … and this is now being spelled out in studies here in the District where there are white kids who are a distinct minority in predominantly black schools, wherever you are a minority you are apt to run into the normal kinds of being the butt of children's cruelty.

So, I was very aware of being a minority, a light skinned minority among the kids in school. One of the ways that the other kids in school would enforce this kind of pecking order, they would say, "Black is honest and yellow is dishonest." You know, meaning that you are illegitimate and this was supposed to make you feel terribly ashamed. The very term, "yellow" was meant to be a term of insult.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, the fact that the Fitzgeralds were a prominent family and that perhaps you could say that economically their class was somewhat above the average Afro-American, did this make any considerable difference in your life in Durham, interrelations with black people and the kinds of business associations that the family might have with white persons?

PAULI MURRAY:

By the time that I came along, there was a fairly good nucleus of a Negro, or in those days they called it "colored," a colored middle class business and professional community. By the time that I came along, the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company was well established. As a matter of fact, as a junior and senior in high school, during my summers I worked as a typist in North Carolina Mutual and many of the kids in high school worked in the summer in the North Carolina Mutual Company.

The Mechanics and Farmers Bank was established, we had Negro doctors, lawyers, an editor of a newspaper, there was the Bankers Fire Insurance Company, Durham was then called "the Mecca of Negro business." So that what I am really saying is, that there was a middle class to which my family belonged, more or less. Within that middle class, however, the Robert Fitzgerald family, of which I was the grandchild, might be called "the respectable poor." We were not business people.

My aunts were widows, my grandmother and grandfather were very frail and elderly and lived on his tiny Civil War pension, which was about twenty-five dollars a month. So, money was hard to come by, we didn't have a car, we didn't have a cow, we didn't have a horse or buggy, we were really the respectable poor. But our values were middle class and therefore, to that extent, I think that there was polite interchange, there was neighborly kindness, but there wasn't social visiting back and forth between the kids who lived in The Bottom and me. Does that give you an idea?

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Yes. One thing that interested me about Durham and segregation was a comment that you made about schools and you said, regarding the textbooks and materials, that "it wasn't so much the hardships that hurt, but the contrast between what we had and white children."

PAULI MURRAY:

Well, this was true. I'll never forget West End School. It was a rickety old wooden built building with the paint peeling; I can see those scales now. You know how wood or shingles or paint blisters and I can see it. When there was a wind in a storm, you could just hear the wind blowing through that old building. I think that it was a two storey building, it might have been a three storey building, but anyway … And of course, the white kids school, a nice brick school sitting in a lawn surrounded by a fence. West End was up on a sort of clay, barren ground. There was no lawn whatsoever. It just sat on clay. The fact that I can remember this today and I can see that old school building there, no swings, nothing to play with when you went out …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

And I imagine that there was quite a walk to school for you?

PAULI MURRAY:

Well, let's see …I guess that it was about a half a mile, maybe more than half a mile. You know where West Main Street is and you know where West Chapel Hill Street is and you know where Morehead Avenue is, well, I had to walk from almost Morehead Avenue, north to almost West Main Street to get to old West End. So, I guess that it was a good half hour's walk.

As I say, it was the contrast between the treatment we got and the treatment that the white kids got and particularly the way that we were treated in the newspapers, you see. I think that I described that in Proud Shoes and I said how if they were going to talk about Field Day or any citywide activities of the school children, most of the space would be given to what goes on with the white kids and then down at the bottom there might be a little paragraph on what happened in the colored school. You sense those things, you feel them.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

As an adolescent, despite these experiences, did you still feel that you wanted to be an individual, just a child who could enjoy growing up and doing the things that children or teenagers did, or did you become so disturbed by these contrasts that even in high school itself you felt that perhaps in your later life you might want to do something about segregation or about racism?

PAULI MURRAY:

I think that I operated on two levels. I was an all round athlete, I was the editor in chief of the high school newspaper, I was a member of the debating club, I was involved in most of the things that kids are involved in. I enjoyed doing these things, but underneath I hated segregation so that all I wanted to do was to get away from segregation. When I graduated from high school, my teachers …let me back up and say that my generation of high school kids were the beneficiaries of probably the post-First World War college trained colored teachers. So, while I was in high school, we began to get a lot of Howard University graduates and Wilberforce graduates also Talledega, and this was probably the first time that the schools were actually being almost fully staffed with college trained teachers.

So, we had a large contingent of Wilberforce graduates there. When I graduated from high school with honors, the Wilberforce Club got together and bestowed a scholarship upon me to go to Wilberforce and I turned it down.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

I see.

PAULI MURRAY:

No more segregation for me. I was fifteen, but that I knew.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Turning it down, did it have anything to do with persons in your family or other persons in that school that influenced you during your youth? I recall the remark that you made about the family and that was that there was pride on both sides of the Fitzgerald family, "but my greatest inheritance perhaps was a dogged persistence and a granite quality of endurance in the face of calamity." Now, these kinds of strengths that you felt from the Fitzgerald part of your family, I mean, were there particular persons that had such enormous influence on you within the family that they would make you feel some inner compulsion to move towards something that was not segregated also, or were they more the teachers who had been in separate institutions?

PAULI MURRAY:

I suspect that it must have been kind of a painful decision for me to make, to turn down a scholarship to Wilberforce, because so many of the teachers of the Wilberforce Club, who were my teachers, were my favorite teachers. I loved these people and they had been ' tremendous role models for me. They were the first young teachers, you know, young and bright and full of life and really opened up new worlds for me. So, the fact that I didn't want to go to Wilberforce, for no other reason than that Wilberforce was going to be a segregated school, since the people that I liked best were from Wilberforce, says something about this deep internal thing about segregation.

Now, remember that my great-grandparents, Thomas Fitzgerald and Sarah Anne Burton Fitzgerald, were an interracial marriage and so, segregation was something that tended to split what to me was my roots. You will also recall in Proud Shoes that I talked about families being split, some families disappearing into the white race. So, this whole business of separation was something that was deeply personal to me because it split my own family. You asked me about color differences.

Color differences operated not only between an individual and the local community, but they also operated within a family. I recall, for example, that I told you there were six of us, six little Murrays. On the one visit that I made back to Baltimore, when I was about nine, it was very clear that at least four of us could go downtown to the movies on Saturdays, the white movie houses.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

And sit wherever you wanted to.

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes, and two of us couldn't. I happened to be one of the two and that says something to you about why I would become a crusader for civil rights. I don't think that I thought that in those days, but I'm sure that these experiences coming to me out from the intimacy of the family made an even greater impact than they would had they been from the society per se.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Did any members of your family, the family with which you lived, or the teachers who had come from Wilberforce, understand this need to at least attempt to have broader opportunities or more choices, the search for options, the move away from segregation? Were they hurt, did they try to get you to accept the Wilberforce scholarship?

PAULI MURRAY:

I imagine that my teachers from Wilberforce were temporarily disappointed, but my recollection is that they followed with interest my career wherever I was and if they were disappointed, this was only a temporary kind of thing. As for my family, Aunt Pauline, and I bless her memory for this, from the time that I was very, very small, allowed me to make my own choices and suffer the consequences. '

I remember that this first visit to Baltimore that I told you about, she wanted to get me a winter outfit and she was now in Baltimore where there were more styles, a big kind of Middle-Atlantic city, and Hub in Baltimore was the store where she took me to buy my winter outfit. What did I want? A chinchilla coat with a red flannel lining and a funny little Tyrolean hat, it was probably from the boys department. She let me buy this conglomeration. [Laughter] And I had to wear it and no matter who laughed at me, that was my choice. Well, that was Aunt Pauline, this was the way she trained me. [Laughter]

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

I can imagine you in that outfit. [Laughter]

PAULI MURRAY:

After World War I, somebody gave me a GI's overseas hat. Did you ever see these big World War I hats, big, broad brimmed with a tall stovepipe?

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Yes.

PAULI MURRAY:

Somebody gave me one of those hats and I loved it. It had something like a cord or elastic that you could put under your chin, with the braid and so forth. I'm sure that I looked just like Little Abie because the things would come down right over my ears, you know. I wore it everywhere except to church. That was the one place that Aunt Pauline drew the line. So, there was a certain comical quality about this child and a certain determination to do certain things and Aunt Pauline tended to let me make my own choice. So, she let me make the choice of what college. And she would support me.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, what made you have a broader conception of your possibilities …

[END OF TAPE 1, SIDE A]

[START OF TAPE 1, SIDE B]

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

I was asking you about what made you have this broader conception of the possibilities for you socially or economically. Most people tended to assume that it was a great opportunity if they could go to any college, even if it were segregated. Did it have something to do with the fact that you had a very mixed heritage, or did it have something to do with the character of your grandfather, the character of Aunt Pauline?

PAULI MURRAY:

I think that it had a lot to do with all of these things. I think …and I'm not even sure that this was conscious at the time, I think that my grandfather played …well, obviously, a person who would wait until she had more or less made her own name and then sit down and write a book about her grandfather, says something about the impact on her life. He was kind of an enigma to me. That is, I was very ambivalent about him.

I resented him and admired him. Here was the impact of this person. I'm sure that this was maybe an unconscious kind of force that may have been moulding. Aunt Pauline's understanding to allow me to be free to think my way through things and make choices, and then support me as far as she could, I think, was another factor.

A third factor was something as small as this, I mean, as seemingly insignificant as this, but it was very important to me. One of my favorite teachers came back to school in the fall with one of these long coat-like sweaters that they used to wear in those days, and it had a "C" on the sleeve, this was some college letter, I asked her what the "C" stood for and she said, "Columbia University." I asked her about Columbia and she told me a little bit. '

Now, what I didn't know was that she had probably gone to summer school at Columbia's teacher's college and bought this and put it on her sweater, but just this little bit was something that opened my vision so that I wanted to go to Columbia. That's all that I knew. All that I knew was that Columbia was in New York City. I didn't know that Columbia didn't take girls, that girls had to go to Barnard. [Laughter] All that I knew was that there was a Columbia University and my teacher had been there and that was where I wanted to go.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, had she been one of your favorite teachers?

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes, she had been one of my favorite teachers and I admired her tremendously.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

I see.

Now, are there any other matters that you think are significant about your childhood experiences and your ancestry that we ought to talk about before we move on to New York?

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes, I want to, particularly in light of some of the experiences of young blacks today, I want to make one or two comments about identity. I am not aware of the kind of identity crisis for many of us in my generation as has been suggested about young blacks of the present generation. I think that we had a very strong sense, and Ralph Ellison says the same thing and he's my contemporary, he grew up in Oklahoma where there were segregated schools. We had a very stong sense of our identity. Booker T. Washington, Paul Laurence Dunbar, these were very significant people in our lives.

We had no self-consciousness about reciting Paul Laurence Dunbar in dialect and as a matter of fact, the person who could really recite Paul Lawrence Dunbar with all the flair of his dialect, was considered a very talented, gifted person. I remember my classmate, Betty Hicks, I don't know whether she's retired now, but Betty Hicks worked for North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company and Betty was really a genius at reciting Paul Laurence Dunbar.

I've often thought that if someone could have discovered her when she was young, she would have made a great dramatic actress. But what am I saying? We did have this sense of racial identity. I remember in our family, finding these little pamphlets, "Thirty Years of Freedom," and then a second little pamphlet, "Fifty Years of Freedom," and these were little playlets that had been written up for community groups to dramatize. One must have referred to about 1890, or maybe 1895 and the other one must have been 1910 or '15.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Are you saying that despite the problem and the harm of segregation that also there were many things of value that came out of the fact that black people were so close to each other and was there in fact something even comfortable about that black community, that community that was totally black?

PAULI MURRAY:

I am sure that there were many positives about it, as I think, for example, of the social life and the community life, I think of White Rock Baptist Church, St. Joseph Baptist Church …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

A.M.E., the A.M.E. Church?

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes, the St. Joseph A.M.E. Church, Mother Zion A.M.E. Church. I think of many kinds of community activities that took place in these community centers, so to speak. And these were comfortable. The point at which life became unbearable was in the contact with the white world, in the sense of business contacts, or going into the community and being made to feel inferior by all the signs and symbols and the etiquette, the racial etiquette in terms of being called by your first name or people addressing adult Negroes as "Auntie" or "Uncle" and maybe "boy" and this kind of thing.

In the relationships between the superiors, the school official superiors and the teachers, and since I had so many relatives who were teachers, I was very aware of the hierarchy of the relationships and the interracial relationships in the school system, the superintendent or supervisor who comes in and calls your teacher by her first name. This, I think I talk about in Proud Shoes. So, the hatred of segregation was not hatred of community life among Negroes, it was finding barriers that hemmed you in, that you were not free to go and come as you chose. Does that make sense to you?

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Yes. And in fact, would I be taking liberties if I said that you had a sense that people were building a sense of community and that this was something that would happen regardless of the outer environment, that people would continue to associate with each other and be proud of their heritage and have a sense of identity?

PAULI MURRAY:

Now, I must say this. In my house, I always heard about the race, "You can't keep this race down. This race is going to show the world yet." The race, the race. So, I called my aunts "race women." There was that sense of loyalty and dedication to the advancement of the race. So, there wasn't a negative feeling about my racial identity in my house and yet, this strange tension between acute awareness of a mixed ancestry and this devotion to "the race."

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

But since the race was so much of everything …

PAULI MURRAY:

Right.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

…and you have always lived with this complexity and these paradoxes, it was something that I guess we all learned, to not only live with but to enjoy and grow from that experience. Now, tell me about going to New York. You were on your way to Columbia but you ended up at Hunter.

PAULI MURRAY:

Right. Well, I said that I wanted to go to Columbia. So, Aunt Pauline took me to New York and she carried me to Columbia and I am sure that the Columbia registrar snickered and sent me over to Barnard. Aunt Pauline trotted with me down the street and over to Barnard. I'm sure that they asked Aunt Pauline a few well directed questions and knew clearly that we were not of the financial means to afford an education at Barnard and so, they said to her …and I'm sure with great desire to be helpful, they said, "Well, where you probably want to go and need to go is Hunter College, because Hunter College is a free city university."

So, Aunt Pauline took me over to Hunter College and there I discovered that I had to have certain entrance requirements. Three years of one language and two years of another and four years of English and Hillside Park High School in Durham at the time was only an eleven grade school. In other words, only three years of senior high. It obviously added the fourth year some years thereafter, but I had only really had eleven years of public school. And so, what it amounted to was that they were referring me to go back to high school and complete the twelfth year and at the same time, if possible, to make up anywhere from one to two years of requirements that I would need for Hunter, Hunter in those days having a very high entrance requirements and a tremendous reputation for turning out future teachers.

So, Aunt Pauline's cousin, you would probably know the sisters Adeline Reynolds Spaulding and Agnes Reynolds Mauney. Well, Adeline's oldest maternal aunt lived in Richmond Hill, Long Island and this aunt loved my mother Agnes.

There was a great affinity between the two of them and she had also lost her one daughter. She had three sons, but she had lost her little daughter, I guess in childbirth …not childbirth, in infancy …and the combination of her devotion to my beloved, but departed, mother and the fact that I was about the age of her daughter and the fact that she was also devoted to my Aunt Pauline, she volunteered to take me and let me stay with her and go to high school and finish off this year in order to qualify myself for Hunter.

Then, of course, we discovered that you had to be a legal resident of the city of New York in order to go to Hunter College. So, she and her husband went to the extent of legally adopting me, through all the legal steps of legally adopting me in order that I might be a legal resident of New York, in order to qualify for Hunter College.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

So, in one year then, you finished your requirements?

PAULI MURRAY:

I finished all these requirements in one year, did about a year and a half in one year and entered Hunter not the next year, but there was a year in between. That year in between, I came back to Durham in order to work to save money and help Aunt Pauline with the expenses of the house and to save money to go back to Hunter. That was the year that I worked at what was then called Bankers Fire Insurance Company. I don't know what it is called now, but it is the leading Negro fire insurance company in Durham that is now housed in the North Carolina Mutual building.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

You were typing there?

PAULI MURRAY:

I was a typist, I was a junior secretary-stenographer.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, you attended Hunter College and were there any particular people at Hunter College that influenced you in regard to your major, or did you just decide that you wanted to write and were interested in journalism? How did you move to that point?

PAULI MURRAY:

I had always had an interest in writing. I had been writing on tablets from the time that I was a little tot. I even wrote a novel by the time that I was thirteen or fourteen. A horrible thing. [Laughter]

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

What happened to the novel? You've hidden it in your files?

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes. [Laughter] Oh, it even got published …Louis Austin, who was a character in himself and it's too bad that you didn't have a chance both to meet him and document his life, but you recognize the name, the late editor of the Carolina Times. What is it, "The Truth Unbridled."

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Everyone talks about Louis Austin.

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes, well, it was one of my first thoughts …I worked for the Carolina Times for awhile as "office boy," custodian, sweeper, cleaner, editor, and during that period, he published and ran in serial form this lurid little novel that I wrote.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

What was the name of it?

PAULI MURRAY:

The Angel of the Desert, I think it was and it was the most stereotyped thing. The heroine, wouldn't you know, was blonde with blue eyes, golden hair, you know, a real little sort of Evangeline or whatever you want to call her, a Little Eva. The wicked sister was a brunette with dark hair.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, when did you write this?

PAULI MURRAY:

Oh, when I was about fifteen. [Laughter] What I'm trying to say is that I had this sense of wanting to write and actually in college, I decided that I didn't want to do anything but write.

So, I didn't take any of the ed courses and I avoided all the psych courses, I took none of the courses that would prepare me for teaching, but all of the courses that I thought dealt with literature, such as "Creative Writing," "Short Stories," "Shakespeare," this kind of thing. Now, there were several individuals at Hunter was really made all the difference in the world for me. One was Lulu Burton, Lulu Burton Bramwell she was when she died. She was my freshman classmate.

She was a Negro. She was as bright as a button, wrote beautifully, spoke beautifully, was on a level with her classroom peers. Now remember, I'm a little southern child who has come up from the South with atrocious English. Despite a certain amount of background and whatnot, still atrocious grammar and constantly feeling the gap between my educational level and that of these bright kids at Hunter college. Because in those days, the New York City high schools were supposed to be the first or second best in the country. So, I could feel this tremendous gap.

Well, here was a girl of color who was right up there with her classmates and think of what this must have done to restore my sense of …the best thing that I can say is "group worth." In other words, all the doubts that I might have about my capacity or equality or whatnot on racial grounds, were cancelled out by seeing someone just like myself who was as competent as everybody else around me. This, I might say, would be the one big hurdle that a child coming out of a segregated school system would have to make. That child didn't know whether he or she was equal to his white counterparts, because there had never been any opportunity for him to find out.

So, way back in the back of his or her mind was always, "Have I got it?" So, in college, which would be the first, or even in high school, in my high school experience in my twelfth year, I would be somewhat preoccupied with whether or not I had the same ability as whites did. So, this was where Lulu was such a tremendous experience for me. Moreover, she loved English, she loved literature, she was an English major. She wrote poetry and introduced me to a great deal of poetry. We read Langston Hughes together, Countee Cullen. She began to introduce me to both black and white poets. So, I owe her a great deal for the awakening of my …of another stage, a more mature part of my literary interest.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

As you spoke about this awareness, something else came to my mind. This is certainly the period in which there is a possibility for hostility. During this period in New York City, of course, and what was happening in the United States, was economic depression, really, the New Deal had not come to the forefront and you are at a city college where you are not with the elite, certainly, who are not affected by this.

Did you find a great deal of hostility from classmates, from white classmates? Did you find them simply not associating with you or did you find teachers who were hostile towards you, or anything such as that? If for no other reason than the simple economic competition.

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes. The first thing that I want to say is that Hunter College was a girl's school, a woman's college. In those days, it was called "the poor girl's Radcliffe." Out of 7,000 women …Hunter College was known to be the largest women's college in the world, out of 7,000 women, only about 45 of us were colored. So that we were not …there were not enough of us, we stuck out, we were not quite a novelty, but we were not in any competitive sense, so to speak. My memories of Hunter are very pleasant.

There were people who sought me out, and I am looking for one of them now, who made me feel like a person. Also, don't forget that it was a day school, a commuter school. It was not a campus and therefore, one probably would miss many of the incidents or opportunities for exclusion that you would get on a college campus. We used to say that our campus was the size of a postage stamp.

One didn't expect to be a part of the sororities. One could aspire to be a member of an honorary fraternity, which I was, Sigma Tau Delta which is the English honorary fraternity. There were two or three rare people who were very meaningful to me.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Let the record tell that Dr. Murray has a copy of her annual yearbook from Hunter College, 1933, that includes pictures of her classmates and herself and indicates that she was in an honorary society.

PAULI MURRAY:

Ruth Goldstein …note the caliber. Ruth M. Goldstein. She was honorary society, Phi Beta Kappa, editor of Echo, which was the school literary magazine, vice-president of the Makeup Box, which was the school theatrical group, and you can just see this long list of credentials. She graduated summa cum laude. Ruth just retired from teaching high school two or three years ago and we are still in contact. She was one of my favorite people in college. She is a great editor now, today, but she gave me my first break. She published my poetry and she published an article that I wrote.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, she published this in school papers?

PAULI MURRAY:

In school papers, yes and I will always remember her with just great love and affection and admiration. I was looking for her picture, a big picture of her, but it is the same picture as this, the one that I showed you.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Well, the honorary society that you mentioned that both you and Ruth belonged to, now this had to do with your gradepoint average or what?

PAULI MURRAY:

It was the national English honorary fraternity.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Oh, English.

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes. I presume that it might have had to do with your gradepoint average and the fact that you were an English major and you couldn't get to be an English major at Hunter without making a certain minimum average. The first two years, you were not allowed to even declare as an English major until your junior year. You had to take a backup major. My backup major was history and if you made the grade and were admitted to the English department, then your backup major became your minor.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, the name of this society was?

PAULI MURRAY:

Sigma Tau Delta. I think that's the sequence. Sigma Tau Delta. There were several teachers who inspired me at Hunter. And these were white teachers, now. One was Catherine Riegart, who is now retired and living, I think, in Florida.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

And how would you spell that?

PAULI MURRAY:

R-I-E-G-A-R-T. Catherine M. Riegart. She was a young teacher, a comparatively young Ph.D., when I met her. I met her in my freshmen class and she gave us weekly themes, essays. You know what I mean, what freshman composition is. And every week, they came back, "D", "D,", "D."

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

And I assume that "D" is the same as "D" for us now? That's poor.

PAULI MURRAY:

Very poor. And evidently, she must have seen something in me, so for Christmas vacation, she invited me and Lulu Burton to her apartment for a tea, in the Village [Greenwich Village]. I had never seen anything like this before.

I had never seen a modern …what do you call it, a sort of artistic apartment, efficiency apartment with all kinds of bric-a-brac that she had from her travels. She had taught in the Girls American College in Turkey or somewhere like that and she used to laugh and say that she lost her college education crossing the Bosporus, which meant that the boat with all of her college notebooks and textbooks went down to the bottom. [Laughter] She had these marvelous little tea cakes, which I had never seen before, you know, the kind in different shapes and covered with chocolate and she served tea in a nice little tray and all of this was just an entirely unknown world to me.

In a sense, her recognition of us as persons, some message came across to me, what it was, I don't know. Those themes began to be "C-", "C", "C-plus", "B-", and the last one was an "A." The last essay was an essay on my grandfather. I got a "B" for the course and that essay was the germ of Proud Shoes.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, I don't want to be a cynic, but I do feel like I have to ask if you think there was something that she sensed, even though she was giving you "D's", prior to this period of time in which you had tea and talked and were in her apartment, or was it something that she sensed after that afternoon together?

PAULI MURRAY:

I think that she saw in my work, she probably saw in my work, flashes of ability, but abominable mechanics. It was my grammar and probably my spelling and my punctuation that was so poor. I think that she was probably intrigued by this youngster, that was such a complex of …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Communicating a lot but not having the skill to do it in an effective way.

PAULI MURRAY:

Right.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

I see. Did she make copious comments on your themes?

PAULI MURRAY:

She must have, and I must have …I mean, the fact that there was this steady development must have meant that I was responding to her encouragement, you see. Remember that this is many years ago, but the two things that stand out in my mind, are this being invited to tea and this steady progress from "D's" up to the "A", and the fact that this essay was about my grandfather, and probably the first time that I felt free enough to talk about something that was meaningful to me and this in turn, evoked her recognition that maybe there was something creative in this child.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

That's beautiful.

PAULI MURRAY:

One other experience I had in college I think is worth recording. We had a marvelous young teacher in anthropology by the name of Dorothy Keur. I could have completely missed up on anthropology but I had a very dear friend who was a science major and loved anthropology and she recommended that I take it and so, I took it as an elective and Dr. Keur, for our field work, had us go once a week over to the Hall of Man at the Museum of Natural History over on 87th Street across the park. It was a marvelous hike because Hunter was at 68th and Park Avenue.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Across the park?

PAULI MURRAY:

Across the park. In those days, there was no problem whatsoever. You could sleep in the park. I have slept in the park. We would hike down to the park and sleep over night, but remember, I am talking about over forty years ago, pre-World War II. We would spend once a week in the Hall of Man, particularly with African villages and village life and art and artifacts and American Indians.

Now, I have touched upon the other two streams of my ancestry, growing up in a kind of European dominated a society and my American Indian ancestry and my African ancestry being more or less suppressed. This experience in anthropology did more for me, I think, than maybe any other course in college, because first of all, it showed me a comparative view of man and how man responds to the environment in which he lives, to build his homes, his art, his institutions and whatnot and I could see the parallels between American Indians and Africans. Secondly, in a sense for me, it removed them from the column of what I needed to have any sense of being embarassed about.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

That's interesting. This Professor Keur, do you have any idea with whom she studied or what …not all anthropologists took that kind of approach at that period.

PAULI MURRAY:

She was a marvelous person. She's still alive and just recently …oh, she retired, I guess, a number of years ago, but I think that she may have studied with Ruth Benedict, I don't know. She studied at Columbia, I'm fairly sure. Her husband was an archeologist, they spent a lot of time in the West …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

On what they called digs?

PAULI MURRAY:

Right.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

And field trips.

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes. And she had a sense and she transmitted to me a sense of the unity of mankind and I've never lost that. This may make me a loss to militant racial identification, but this sense of unity within mankind, this sense of seeing mankind as mankind …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, it is not always the case that college students take all of their courses seriously. Did you take all of your courses seriously, or were there a few that you decided to really study and others that you just kind of let slip by or something like that, was it the interest in your background that made you work hard on this anthropology or did you approach all of your subjects in that manner?

PAULI MURRAY:

I'm sure that I did not because I have a college record that ranges from "A" to "C". Part of this was because I was a working student and …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Where were you working?

PAULI MURRAY:

Oh, I worked at the Alice Foote McDougal Coffee Shops, I was a dinner waitress and then …I was a freshman, my freshman year was the year of the stock crash, October, 1929. I bounced around from job to job, waiting tables here, washing dishes here and running elevators here …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

You were lucky to find any job.

PAULI MURRAY:

Right. Yes, I was always working.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

You don't know how lucky that was. [Laughter] Now, did you stay out on Long Island?

PAULI MURRAY:

No, I had moved to the YWCA in Harlem by that time and for a lot of my college career, I lived at the YWCA, West 137th Street, Emma Ransom House, it was called in those days. I'm trying to think of the question that you asked me …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

I was asking you whether you approached all your studies in a serious manner.

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes. As I said, they went from "A" to "C". If a teacher was boring, I was just as apt to make a "C" in a course. If she was challenging, I was just as apt to make an "A" in the course. If the course challenged me to be creative, I was apt to make an "A". If the course was of subject matter that I thought was interesting, I passed the course even though I only made "D". For example, this second half of that anthropology course was a highly technical course on evolution, you know, the various classes, the whole story of evolution and this was highly technical. I could barely, I had no science background for it, but I happened to make it through that course with a "D". For me, that "D" was like an "A-plus", because I really …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Because you made it through.

PAULI MURRAY:

That's right. Now, when it came to educational psychology, I couldn't have cared less. There were just certain courses that I wasn't interested in. History, I liked.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

You said that was your "just-in-case-major."

PAULI MURRAY:

Right. So that turned out to be my minor. I loved classics, which would be really the history of culture. Apparently, I guess that one might say that I had a pull toward the humanities, although I would not have known how to define them in those ways. I certainly had no interest in math, possibly less in economics, but I was a good political science student. So, it would range between the social sciences and the humanities.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, you attended Hunter College and then after being graduated in 1933 as an English major, nearly a decade elapsed before you made your decision to go to law school. During that period, you became what I consider an accomplished poet, after having read some of your poetry, and you were inspired by such poets as Stephen Vincet Benet and Langston Hughes…

PAULI MURRAY:

And Countee Cullen. And what's the West Indian … Claude McKay.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Yes, Claude McKay. I take it that you knew some of these people.

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes, I knew Langston and I knew Countee.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, your poetry was of a varied character, such that one might infer …and this is, I repeat, inference, moments of dissatisfaction, disappointment, doubt, but also a fierce determination and insistance upon some sort of action, demand for solutions or some resolution to problems that you saw within not only your own society, but perhaps even in a sense of the world as you knew it within the anthropological sense. In 1933, you wrote a poem …

PAULI MURRAY:

Me?

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Yes. I'm not going to read the whole poem, but …

PAULI MURRAY:

It's come back to haunt me. [Laughter]

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

I'll read just a few excerpts. "Youth, 1933". "I sing of youth, imperious, glorious, dissatisfied, unslaked, untaught, unkempt youth. Youth who admits neither God nor country, youth proud and eager, proud of its broken heads, eager to martyr itself for any and all causes. On they go, this youth, the world over, headed for chaos, with wrangling and smiling, bursting all bonds, junking all ideals, shouting in chorus, ‘We protest. We demand,’ Having one weapon, they wield it unsparingly. Youth, hotheadedness, energy, passion. Make way, you slackards, money hounds, party guns. We are your leaders. Trust or outlaw us. We are the youth of the world's New Deal."

PAULI MURRAY:

That's one of the biggest pieces of schizophrenia I think I've ever heard. [Laughter] Because you recognize that I am standing off looking at myself as well as my generation.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, I also want to read part of another poem written in the same year, you might be able to guess this one, too, "The Newer Cry."

PAULI MURRAY:

Oh, yes.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

And then I would like you to just simply talk about these two poems and …

[END OF TAPE 1, SIDE B]

[START OF TAPE 2, SIDE A]

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

In my paperback, "The Newer Cry" is on page 55.

PAULI MURRAY:

Do you know that the editor died last week …I mean the publisher. My agent for this died in November and the publisher died last week, Bill Atkin, President of Silvermine Publishers.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, I'm going to read another excerpt from a 1933 poem, from "The Newer Cry," and then I was asking you to simply comment on these two poems. You've already begun to comment on how "Youth" represented your standing back and looking at yourself and you call it, in a sense, schizophrenia, but I would like to juxtapose an aspect of "The Newer Cry." "Let us grow strong, but never in our strength forget the weaker brother. Let us fight, but only when we must fight. Let us work, for therein lies our salvation.

Let us conquer the soil, for therein lies our sustenance. Let us conquer the soul, for therein lies our power. Let us march in steady unbroken beat, for therein lies our progress. Let us never cease to laugh, to live, to love, and to grow." That also was written in New York in 1933.

PAULI MURRAY:

I'm sure that both of these poems were probably written at the switchboard of Hunter College after I graduated. I had the rather dubious distinction of being the first Negro to have been employed in anything but a broom and mop job. It was quite a step forward for Hunter College to employ me as the evening switchboard operator. I sat there at the evening switchboard and wrote poetry between calls. "Youth, 1933" is one and I think "The Newer Cry" is probably the second. "Youth" was expressing my sense of identification with the whole class of youth, the world of black, white, international Communist youth, European, wherever.

"The Newer Cry" was expressing my racial identity. You will note that in both of these poems, I am troubled by a sense of the violence of revolution, the destructiveness, and I don't know whether you've noticed this, but it runs all through my poetry of this period. I don't know whether you've read "To Poets Who Have Rebelled."

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Yes.

PAULI MURRAY:

It's the same thing, "protest if you must, but at the same time, let your throat ache double with the cry of beauty here and now." Here is a child that was brought up essentially close to nature and essentially, I think, with great freedom and a sense of love, being surrounded by loving people in one's environment. And never really relinquishing this longing for love in however a way you wished to describe it. Love as the great instrument of change and whatnot.

I think that it comes out perhaps more in "The Newer Cry" than it does in "Youth, 1933." Because in "Youth, 1933" I'm really talking about my contemporaries, the young Communists, the young Socialists, the young radicals. In "The Newer Cry" I'm talking particularly, I guess, about the protest literature that is being written and so much of it is so heavily weighed with the protest of being a black person in America at this time. For me, you can see that always responding to challenge. You say I can't and I'll show you I can even if I die trying. This was my attitude toward America and so was it Claude McKay's.

You know, "I must confess I loved this cultured hell which tests my youth, although she feeds me bread of bitterness and sticks her tiger's tooth into my …", whatever, "I must confess I love this cultured hell." Well, this has been my attitude toward America. I love America and whatever she hands me, I'm handing her back with, I hope, a championship quality. So, so many of my heroes, my racial heroes, have been the champions, the Jackie Robinsons, the people who climbed over and said, "I'll show you."

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

For the sake of all those who may in the future listen to this and not be able to understand, perhaps because of the circumstances under which they listen to it, let's go into a little bit more about "I love America." You are saying, "I love America" for a particular kind of reason. Was it really America as it was actually, with violence and with all the problems of society, all the injustices, but can you explain more about what it was?

PAULI MURRAY:

Well, I mean by saying that "I love America," that first, it is home. No one can be more native to America than America's black population, because America's black population biologically is all of the great streams of mankind that make up America. The first American, the indigenous American, by this time there has been so much recirculation of genes that we are all mixed up.

We all have Indian, European and African ancestry. Secondly, traditionally, black Americans go back to the very beginnings of America. Our blood and our sweat and our tears and our memories are built into the country and I maintain that Africa has already made her contribution to America, that America is as she is today, culturally, because of the presence of black Americans. The impact upon speech, the impact upon customs in the South. America would have been a different country without the presence of blacks.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Yes, even though it was involuntary, it was something that left an indelible imprint upon America.

PAULI MURRAY:

Right.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

And of course, as you said, that as much as we are built into it, we built it.

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes. All of this, then, plus America's dreams. Some people might call it her pretensions. I want to see America be what she says she is and I consider it part of my responsibility to do that. It's a kind of patriotism …well, let me give you a symbol of it. When I went down to look at the archives, to look at the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States for the first time, enshrined in the Archives, behind those glass cases, with its honor guard, just as I entered, here was a uniformed black American standing as the guard of honor to protect these two hallowed documents, from the point of view of our history. To me, there was such great symbolism in that, that it was black America who was safeguarding the true meaning of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States. Well, poetic people tend to deal in symbols, but it just happened that this is the way I saw it.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Symbolism and perhaps irony, also.

PAULI MURRAY:

Yes.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

For the most part, we have been the ones who have always most greatly and most fervently …

PAULI MURRAY:

Well, it is that kind of patriotism that I'm talking about, America being what she proclaims herself to be. Be what you are supposed to be.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, in the context of that, before you went to law school, what kinds of activities were you participating in? These are the years after the summer of '33.

PAULI MURRAY:

Well, first I worked for the National Urban League as a special field secretary for its house organ, which was then called Opportunity Magazine. Then …

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Was Elmer Carter still …

PAULI MURRAY:

Elmer Carter, I think by that time, I think that he was then editor of the magazine, but the late Mr. Lester B. Granger, who just died several weeks ago, became the business manager of Opportunity Magazine and I worked immediately under him for that year that I worked with them. Now, this is about '33, '34 and by this time, we are really in the middle of the Depression. I got …ultimately, I got a job on WPA, first working in remedial reading and then switching over to the Workers Education Project.

The Workers Education Project was a tremendous intellectual experience for me, because it brought me into contact with the young, radical intellectuals of that period, young Communists, young Socialists, young Trotskyites, young Republicans young Democrats,, it was a highly politicized project.

Those were the days when organization, when collective bargaining for labor was very important, unionization of black and white workers, black and white unemployed together, seeking to preserve WPA, which was the only basis of employment in jobs that many of us had in those days, a much larger, a much more generalized condition of poverty among blacks and whites and unemployment among blacks and whites then that today.

So, a much closer feeling of solidarity in large areas, rather than the kind of …these were the days before the suburbs, the days before the inner cities being concentrated in terms of blacks, and days in which labor was the out group, in a sense, and struggling for recognition. So, there was much more of a climate of solidarity, interracial solidarity within the radical-liberal part of the population, than we got, say, after the sixties. All of this began to point me toward law.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, while you were doing all these things and meeting with radical intellectuals, did you maintain close contact with your relatives, with your family, your extended family, and your friends in North Carolina and your friends at Hunter? How did this affect those relationships?

PAULI MURRAY:

I would come back and forth, but obviously, I suppose my ideas would tend to be more radical than those of the community that I left. So much so, that when I, in 1938 when I applied to the University of North Carolina, this was met with consternation by my family, my immediate family, primarily because they were afraid that they would be lynched, or that the house would burn down, I think it was real fear, not disagreement with me on principle, and I think that by that time, I was perhaps so far from a … I don't want to say, "sedate," but by that time, I had become a completely emancipated mind, let me say. Fairly independent and no longer willing to come back and be a part of the social milieu of the little community I left. I mean, it was definitely almost "you can't go home again."

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, there is another aspect of Pauli Murray, the former English major now, that would seem to foretell, or from which one might infer a special direction and character of activism, certainly these activities in which you were involved before entering law school did that, a Pauli Murray as a mature adult that I think tends to be revealed in two very short poems, which I'll just read because they are very brief. One called "Quarrel." "Two ants at bay on the curved stem of an apple are insufficient cause to fell the tree." And "Color Trouble." "If you dislike me just because my face has more sun than your has, then when you see me, turn and run, but do not try to buy the sun." These are written in 1937 and 1938.

Now, there are three major incidents prior to your entering Howard University Law School in 1941 that come to mind in connection with these poems and in connection with the work that you did after you left Hunter. Although documentation is available on these, I would like you to discuss briefly for the sake of the record, what you consider the salient issues involved in the following three activities between 1938 and 1941.

First of all, one that you mentioned already, in 1938, your attempt to enter the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, unsuccessfully challenging the exclusion of blacks from graduate school and professional schools at UNC and blacks, of course, not being admitted until 1951 despite the Gaines decision in 1938.

The second is the Petersburg, Virginia bus incident involving your arrest and conviction for resisting segregation on an interstate bus, and the third is becoming field secretary of the Workers Defense League in relationship to the case of Odell Waller, a black sharecropper convicted of first degree murder of his white landlord by a white poll tax jury. We can go back and do those in any order that you would like, chronologically if you like, or in reverse order.

PAULI MURRAY:

What was the first one that you mentioned?

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

The first one is UNC and not being admitted.

PAULI MURRAY:

Well, all of this, these activities, took place, I think, in a highly politicized climate. Remember that I am being influenced by the whole radical intellectual climate of those days.

The organization of labor and the struggle, and I participated in those struggles as a volunteer labor organizer and on the picket lines. I even picketed the Amsterdam News with my dear friend, Ted Posten, because there was a lockout …now this is a black newspaper locking out black editorial writers.

Well, I was on the mass picket line and got my first arrest, got arrested in 1935, I think it was. Well, what I am trying to suggest was that out of this atmosphere of struggle, curiously enough, my militance on race growing out of my exposure to labor struggles and my becoming interested in this. Remember that I talked about labor education and I got interested in the whole background of labor and took off for about six months and went to Brookwood Labor College.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Now, where is Brookwood Labor College?

PAULI MURRAY:

Well, it is no more …whenever I had a concern, I always had to go to school over my concern. I couldn't just read books, I had to find a school and go to school. Brookwood Labor College was in Katona, New York, and it was set up by the American Federation of Labor way back in the first or second decade of the twentieth century, in 1936 it was being supported in part by the AFL and maybe the Committee for Industrial Organization which later became the CIO.

This was where members of trade unions, who couldn't afford to go to college, but who represented leadership potential and ability, would go and get courses in labor journalism, courses in labor economics, in history, you know, this kind of thing. Well, I took myself up there and went to labor college. That was the year, I believe, that Earl Robinson composed "Ballad for Americans," which you recognize in terms of Paul Robeson singing "Ballad for Americans …"

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

Yes, Paul Robeson.

PAULI MURRAY:

I heard one of the first performances of "Ballad for Americans." That was the same year in which the general strike of the United Automobile Workers broke out, 1936-37, I'm not sure, but right in that period and they had the first sit-ins in Detroit and we labor students at Brookwood Labor College became volunteer helpers for the strike in plants at Tarrytown, New York and we would put out strike newspapers and do things of that sort. That was the same year in which the Abraham Lincoln Brigade was organized to fight, American volunteers, to fight for the Loyalist government in Spain, and almost the whole class I was in at Brookwood Labor College, almost en masse volunteered and went to Spain. Very, very few of them returned.

You can think of the impact of that experience on me. All of this is happening, the whole concept of freedom and dignity and I am now beginning to relate this to being a Negro in America and therefore, perhaps in some way, I was catapulted faster into a radical stance. Maybe I jumped a generation or something of the sort, as a result of this kind of hothouse of international labor, political, radical atmosphere in which I …to which I was being exposed.

I think the key fact, the thing that made me really apply to the University of North Carolina …well, here again was a convergence of factors, my ostensible reason, and it always seemed to be this way, that I had some family problem, some personal problem that I was trying to work out and what seemed very logical to me, I then began to follow up on. Of course, the minute that I began to follow up on what was very logical to me, I began to run into road blocks. My aunt really wanted me to come home.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

This is Aunt Pauline?

PAULI MURRAY:

Aunt Pauline and Aunt Sally, Now, they were getting older and my problem was that I wanted to get some more education. I wanted to do some graduate work. Well, wouldn't it make great sense to come home and commute to the University of North Carolina and get a graduate degree at the University of North Carolina, either in social science or in law and that would allow me to fulfil my family responsibilities in Durham.

GENNA RAE McNEIL:

We find that after the futile attempt of Thomas Hocutt under the auspices of the NAACP to enter UNC School of Pharmacy, Pauli Murray, because of a number of reasons, which you stated, some having to do with family, sees it as a logical thing to do to enter UNC in social science or law school. So, in November of 1938, you apply for a catalog and an application and thereafter, what occurs?

PAULI MURRAY:

They sent me an application blank and they had written into the printed application blank, race and religion. This has been typed in so that it stands out apart from a normal form. I think I answered it but may have said, "But what difference does it make?"

Obviously tongue in cheek. In due course, I got back a letter from Dr. Frank Graham, who was the then president of the University of North Carolina, saying, "I'm sorry, but the constitution and the laws of the state of North Carolina prohibit me from admitting one of your race to the law school."° Either the day after or two days after I received this letter, down came the Supreme Court decision in the Lloyd Gaines case. Now, the Lloyd Gaines case decided in December of 1938 was the beginning of the long read back from Plessy vs. Ferguson, the "separate but equal" decision. Lloyd Gaines, in the educational field, was the start of the long road back to the 1954 decision and what it said was: A state has a responsibility to educate its residents.

It cannot shift responsibility to other states by giving out-of-state scholarships. It must give substantially equal facilities to its colored citizens as well as the white or must admit them to the existing institutions. It went on to say that this is a "personal right" and in a sense it does not matter if only one person is seeking it. This, of course, you can imagine …I immediately wrote back to the University of North Carolina and said, "Ah, but here is the Lloyd Gaines case."